There’s an irony in the fact that I do most of my writing at the same desk where I spend most working days. The glass desk surface that bears witness to JIRA boards and video calls is expected, come the weekend, to transform into a portal for creative thought. It’s rather like asking a courtroom to double as a jazz club.

Yet this apparent contradiction reveals something profound about how ideas actually work. Consider this: those interminable Monday morning meetings—the ones where we debate project timelines with the enthusiasm of watching paint dry—often become unexpected catalysts for breakthrough thinking. The very tedium that makes me fidget in my chair seems to activate a different kind of mental processing. My mind, starved of stimulation, starts surfacing connections that focused attention would never discover. These seemingly wasted hours don’t end when the meeting finishes. The ideas they spark follow me into the weekend, settling into the shiny glass surface of that same desk until I can wrestle the emerging ideas into words.

This is the first lesson about creativity: it doesn’t respect boundaries. The constraints of one context can become the catalyst for breakthrough in another.

Trains, planes and automobiles

Trains are a reliable thinking machine for me. Perhaps it’s the way landscapes unfold like arguments, each field and town a new premise, building toward some inevitable conclusion. I’ve noticed that my eyes naturally track the objects that capture my attention: a red barn, a lone cyclist, a flock of starlings lifting from a wheat field. This tracking motion seems to trigger something neurological, a magical shift in mental state that transforms what comes into my head.

At 35,000 feet, the effect is even more pronounced. Through an airplane window, the world shrinks to a topographical map. Cities become circuit boards; rivers transform into silver threads connecting distant dots. This radical shift in perspective—what I call the “uber-macro” view—forces the brain to recalibrate. Problems that seemed insurmountable from ground level reveal their true proportions. Connections that were invisible become obvious. Alain de Botton captured this beautifully in his book “The Art of Travel,” noting how physical elevation can trigger psychological elevation.

Cars, oddly, are different. The creative spark rarely strikes when sitting in a car—unless the journey is particularly tedious. There’s something about productive boredom, that state of unstimulated consciousness, that allows suppressed thoughts to surface. It’s as if the mind, deprived of external stimuli, begins to raid its own archives.

Away from home

But perhaps the most powerful catalyst for fresh thinking is complete displacement—the temporary exile of travel – and I’m experiencing this as I write this. When I’m away from home, everything familiar is stripped away. I become a kind of cognitive immigrant, forced to navigate new systems, decode unfamiliar social rules, and confront the embarrassing limitations of my linguistic abilities.

This displacement creates what psychologists call “cognitive disinhibition”—a temporary loosening of mental constraints that allows for novel combinations of ideas. Away from the comfortable grooves of routine, the mind becomes more flexible, more willing to entertain possibilities that would seem absurd at home.

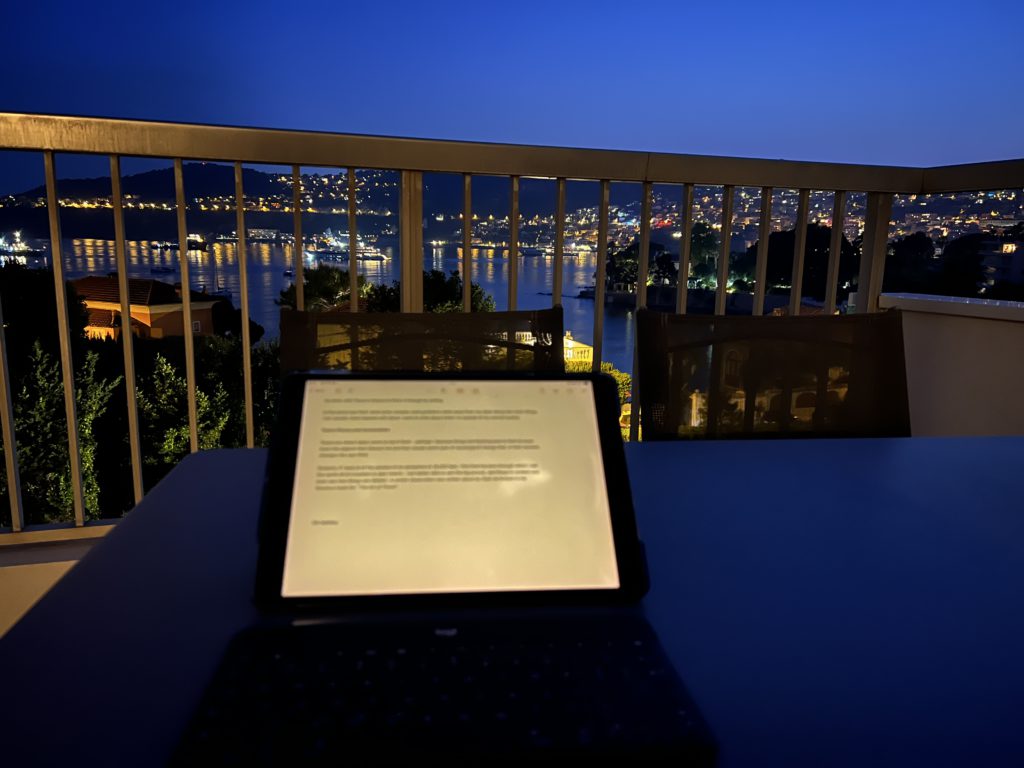

Photo: Writing during a warm June evening in Saint Jean Cap Ferrat

I begin to question assumptions I didn’t even know I held. Why do British people wrap criticism in layers of linguistic cotton wool? Why do we apologize for things that aren’t our fault? These questions, invisible within the system, become blindingly obvious from outside it.

The parallels to scientific discovery are striking. Many breakthrough insights occur when researchers venture outside their home disciplines, when they’re forced to see familiar problems through unfamiliar lenses. The greatest innovations often happen at the intersection of fields, in the cognitive equivalent of foreign countries.

Is the daily grind actually the inspiration, not the constraint?

This brings us to a central paradox of creative work: we often do our best thinking when we’re not trying to think. The constraints of daily life—the meetings, the deadlines, the domestic obligations—aren’t obstacles to creativity so much as the raw material for it. They create the pressure that, when released, propels new ideas into consciousness.

I’m writing this from an apartment balcony (pictured), surrounded by distant conversations in French that I don’t understand, watching people navigate social rituals that seem both familiar and strange. This displacement, temporary though it may be, has already begun to shift my perspective on problems I left behind at that glass desk at home.

Perhaps the real insight isn’t that we need to escape our constraints to be creative, but that we need to dance with them—to use the friction of limitation as the spark for innovation and to give ourselves the time to do nothing so that ideas can crystallise.